Yanderson Granados’ parents look through the files of his death inquiry at their home in Caracas, Venezuela.

Beleaguered regime kills guilty and innocent alike in poor barrios, often with shots to the heart

21 de diciembre de 2017

Juan Forero y Maolis Castro

BARLOVENTO, Venezuela—The young men had already been tortured at an army base when soldiers piled them into two jeeps and transported them to a wooded area just outside the Venezuelan capital.

Stumbling in the dark, with T-shirts pulled over their faces and hands tied behind their backs, they were steered to an open pit. Soldiers then used machetes to deliver blow after blow to the base of their necks. Most suffered gaping wounds that killed them before they hit the ground.

Others, bleeding profusely but still alive, crumpled into the shallow grave as their killers piled dirt over their bodies to hide the crime.

“We think they were alive a good while as they died from asphyxia,” said Zair Mundaray, a veteran prosecutor who led the exhumation and investigation that pieced together how the killings unfolded. “It had to be a terrible thing.”

For Mr. Mundaray and his team of investigators, the massacre in this area east of Caracas in October 2016 was the most bloodthirsty of killings by security forces in a country riven by unspeakable violence.

Prosecutors, criminologists and human-rights groups say it was only one of many recurring and escalating lethal attacks carried out by police or soldiers.

PHOTO: CARLOS VILLALON FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The full scope of the alleged atrocities is beginning to surface publicly now. Luisa Ortega, a former Socialist Party stalwart who was attorney general until fleeing to neighboring Colombia in August, is releasing data on the killings, as are independent human-rights groups and Venezuelan journalists.

Her office recorded the slayings of 8,292 people by the police, the National Guard, the army and Venezuela’s version of the FBI, from 2015 through the first six months of this year, she said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. By her account, the operations target poor barrios that have traditionally formed the bedrock of support for Chavismo, the radical leftist movement in power since 1999 that is named after its late founder, Hugo Chávez. She and other human-rights activists criticize them as misguided and heavy-handed attempts to confront the crime running rampant in those neighborhoods.

Kill Zone

Homicides soar in Venezuela.

Source: Venezuelan Observatory of Violence, with data from the Scientific, Penal and Criminal Investigations Corp.; Venezuelan Attorney General’s Office (Venezuela homicide rate); FBI (U.S. murder rate)

“It’s a systematic policy against a social sector,” said Ms. Ortega. She said the police and armed forces enter poor barrios heavily armed in large numbers, “leveling everything that is in their way.”

The government of President Nicolás Maduro says it respects human rights but must respond with force to battle a soaring crime wave he and his ministers say was hatched from abroad to destabilize the country. Whipsawed by gangs and cocaine, Venezuela has seen homicides spiral from 25 per 100,000 people in the first year of the Chávez government to 70 per 100,000 in 2016. That is the second-highest in the world outside El Salvador, according to data collected by the attorney general’s office and criminologists.

“We can’t let our guard down,” Mr. Maduro said in one speech extolling the operations.

Calls and emails to Ms. Ortega’s successor in the attorney general’s office, Tarek William Saab, as well as to the president’s office and the police, army, National Guard and other agencies weren’t returned.

By Ms. Ortega’s count, Venezuelan security services claimed roughly the same number of civilian lives in the year ended June 30 as did Rodrigo Duterte’s controversial antidrug campaign in the Philippines, a country three times Venezuela’s size.

Forensic evidence from shootings and a chorus of complaints from the poorest barrios indicates the vast majority weren’t acts of self-defense by security forces.

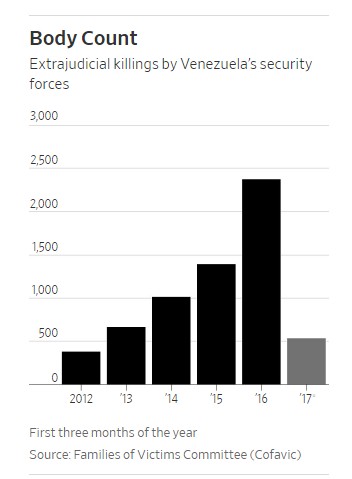

An independent Caracas human-rights group, Families of Victims Committee, or Cofavic, tallied 6,385 extrajudicial executions from 2012 through the first three months of this year, in what it calls legally unwarranted social cleansing operations by state forces.

Fired by Mr. Maduro, Ms. Ortega fled Venezuela in a speedboat to avoid arrest before arriving in Colombia. She recently filed a 495-page report on rights abuses at the International Criminal Court in the Netherlands, asserting that “the civilian population is victim of these criminal attacks.” A copy of the report was reviewed by the Journal.

She now operates a parallel prosecutor’s office, staffed by Mr. Mundaray and other loyal prosecutors exiled from Venezuela, on a leafy street in the Colombian capital. Working with evidence and documents smuggled out of Venezuela, prosecutors say they are advancing on cases of alleged rights abuses and corruption by Ms. Ortega’s former comrades.

Over the past year, Venezuela has entered a severe economic downturn. The output of oil, its lifeblood, has declined for 13 months, skyrocketing inflation has given way to hyperinflation, the currency is virtually worthless and millions struggle to feed themselves. In this context, an increasingly authoritarian regime has resorted to tactics long used in dysfunctional countries to generate public support: military-style assaults on poor districts and a growing body count of people officials assert were criminals.

“State policy is not to catch the criminal,” said Mr. Mundaray. “Because there’s police corruption and no control of the jails or the courts, then they opt to kill them.”

Venezuela escalated its lethal use of force in 2015, when it launched a new strategy called the Operation to Liberate and Protect the People, or OLP. The stated goal, using various police and military units at once to flood neighborhoods, was to defend citizens from foreign criminals and gunmen, though the government never offered evidence of such a threat.

“This is the concept: Liberate the people, protect the people,” Mr. Maduro said in a speech that year.

The OLP strikes were one of many loose strategies criminologists say were employed by the state. What they had in common was the high body count.

To blame the slayings on “resistance against authorities,” the police alter crime scenes and incidence reports to make it appear as if officers were in danger, say investigators on Ortega’s team, criminologists and relatives of the dead.

Mr. Mundaray says he has personally examined bodies and repeatedly seen direct, clean shots to the heart and upper chest at straight angles, which he says clash with reports describing wild gunfights.

“It’s always a shot to the chest, perpendicular, in and out, upper torso,” he said. “That doesn’t happen in confrontations. Statistically, that doesn’t happen.”

Elibeth Pulido said that’s exactly what happened to her son, a 27-year-old electrician named Jose Daniel Bruzual. On Aug. 22, a swarm of officers who said they were searching for kidnappers stormed into her home, according to people in the neighborhood.

Two witnesses told the Journal they heard Mr. Bruzual yelling repeatedly, “Call my mom, they want to kill me!”

The victim suffered one shot to the upper chest, a death certificate shows. Mr. Bruzual’s body was rolled in a bed sheet and carried out of the house. Bullets pockmarked walls inside and outside Ms. Pulido’s small home, pointing to a shootout. The police said a gun was recovered. Ms. Pulido said it was planted, and that her son wasn’t a criminal.

The targets of the crackdown are often in hotbeds of government support, like the 23 of January neighborhood, which is near the presidential palace and was raided in October 2016.

Rossinis del Valle, a 40-year-old mother of six, said officers barged through the fence of her home and front door, hauling out her husband, her brother and a friend with their T-shirts over their heads. Officers shot and killed all three, she and other relatives said.

“All these cases are the same—it’s the same modus operandi—and they don’t care if they have a criminal record or not,” said Ms. del Valle, who said her relatives weren’t involved in criminal activities. “They don’t kill people in rich neighborhoods. They kill people in barrios.”

Not far from her home, 25-year-old Yanderson Granados was picked up in the same sweep, according to his family and police reports. A well-known community leader was a witness, describing in an interview how security forces dressed in black led Mr. Granados into an alley between two buildings. Shots were fired, and his lifeless body was then carried out.

“Everyone here knows,” said the witness.

As in other cases reviewed by the Journal, the slayings in the 23 of January neighborhood had similarities with other operations by security forces. The targets were shot at close range and in direct angles in the chest or abdomen, the Journal review showed. Witnesses describe security forces clad in skull masks. Bullet-holes peppered walls and buildings.

Those killed in the 23 of January operation were discovered by their families in a public hospital, their clothes discarded and their bodies naked. Human-rights investigators say stripping bodies of clothing is a common way to obscure the fact that a gun was fired at close range.

“When there’s a gunfight, you have your body here, the gun there, the shell casings there,” said Yanderson’s father, Asdrubal Granados, who has collected police reports and made complaints to myriad agencies about his son’s death. “No one is supposed to touch it” until investigators arrive. Instead, he says, his son was taken to the hospital morgue and “tossed there like a dog.”

In an address on the day of those killings, Interior and Justice Minister Nestor Reverol announced that 19 people had been killed in confrontations with security forces in what he called a “new phase” of operations launched in 23 of January and other districts.

“We are going to continue the necessary activities to guarantee peace,” he said. “Our victory is and will be the peace.”

Policemen who have participated in the operations say only an iron hand can bring control to unruly barrios. “For them, we’re a trophy—to kill a policeman is to get a trophy,” said one officer.

Sitting in a hotel restaurant in Caracas before a plateful of eggs, the policeman, a veteran of Caracas’s meanest streets, said to surprise criminals the police plan to strike operations swiftly, at 4 a.m., when those being targeted are still asleep. “Imagine the danger,” he said. “We can’t wait for an arrest warrant.”

He resented the concerns rights groups show about the killings of criminals in the barrios. “They worry about their rights and not ours, when we are the ones who get killed,” he said.

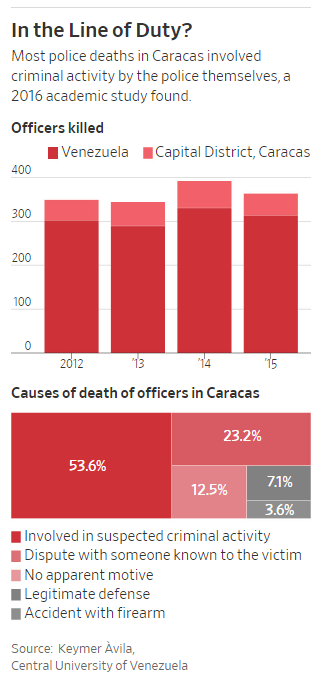

The number of police officers slain is high for a country of Venezuela’s size, with at least 1,700 officers killed from 2012 through 2016, according to data compiled by Keymer Ávila, a criminologist who studies civilian killings by police and the killing of officers. In the U.S., which has 10 times Venezuela’s population, 62 officers were shot dead in 2016, the FBI said, with another four on-duty officers killed.

Mr. Ávila and other leading criminologists here argue the circumstances related to the deaths of many police officers suggest that the security forces are engaged in criminal activity themselves, not that they are under siege.

Mr. Ávila’s 2016 study of police slayings in Caracas showed that seven of 10 policemen killed were off-duty. He found more than half were related to some sort of criminal activity on the part of the officer. Mr. Ávila also found that 31% of the killings were carried out by other officers. Only 7.1% were clearly killed in the line of duty, he found.

With nowhere else to go to complain, hundreds of families of those killed by security forces for months flooded the offices of opposition congresswoman Delsa Solórzano. She headed a special committee that held hearings in which people from the barrios spoke about what had happened to their loved ones.

“Everyone started to come,” said Ms. Solórzano, whose office collects police reports, death certificates and other official documentation of lethal government operations. “Sadly, these things don’t surprise us,” said the congresswoman.

The most notorious case in Venezuela, first reported in detail by a team of reporters from the Caracas news website Runrunes, involved the deaths of 13 young men here in Barlovento, 10 of whom were killed with machetes and buried in a mass grave. Another two were shot, one was tortured to death, and five remain missing.

It began when security forces believed there was “a growing conspiracy against the Bolivarian government,” according to an army document viewed by the Journal. Military authorities believed “an internal subversion” was leading to drug trafficking, kidnappings, robbery and extortion, according to the document.

“The final desired result is that the groups that generate violence be neutralized as fast as possible,” said the document, which is marked secret and was written before the operation.

Carmen Cordero’s son, Eliezer Ramirez, 22, was at home in Barlovento on leave from the merchant marine when he was detained in army sweeps on Oct. 16 of last year along with dozens of others. Prosecutors who later investigated the case and two of the men detained told the Journal the entire group was taken to an army base, where they were beaten with helmets and fists. Soldiers demanded to know about a local gangster.

“We asked for water,” one young man said, “and they put a gun in my mouth.”

Another man who was detained said in an interview with the Journal that at night “you could hear people scream.”

Only after one of the soldiers was interrogated and told investigators what had transpired was the crime uncovered; several soldiers have been charged and are awaiting trial.

“They tried to say they killed a gang, when they were good kids who were clean,” said Ms. Cordero. A maid in Caracas, Ms. Cordero now spends her free time making sure the grave where her son is buried is well-kept and asking herself how this tragedy could befall her family.

“I always say the government has a lot to do with this—they didn’t catch a single criminal,” she said. “What we ask ourselves is, ‘Why? Why would they do this?’ ”

Mayela Armas and Anatoly Kurmanaev in Caracas, Venezuela, contributed to this article.

Publicado originalmente en: The Wall Street Journal