April 22, 2019

Keymer Ávila | @Keymer_Avila

On the first anniversary of the International Workshop on Police Reform, organized by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, held in Mexico City, the full version of the analysis we did for that event is published, entitled: “What happened to police reform in Venezuela ? Basic questions and answers about the process in its pubertal stage ”.

In this work we answer six basic questions about police reform, in this installment we will focus on the first two:

- How do you evaluate the processes of police reform that have been carried out in your country?

Undoubtedly, the impact of the process carried out by the National Commission for Police Reform (CONAREPOL) in terms of designing public policies, with a methodology based on consultation, research, as well as the regulatory products derived from them. they are positive. At the level of duty, the impact is positive because there is a good police model.

At the level of reality, of being, of the construction of institutions and of people’s daily lives, this ideal model has not been implemented and what the de facto political power has done, in parallel, is a counter- reform , that is, do the opposite of what is predicated in the model. This has clearly negative consequences .

- What have been the main results?

The first and most important, which has already been mentioned, is the designed police model , a police force whose objective is respect for civil and professional human rights. Not only does it have a model of what the police should be, but it also left the precedent of a way of elaborating public policy in this matter, based on research and prior consultation, which is based on informed knowledge for the decision making.

Some institutional spaces that did not exist before that could be useful for the implementation of this model were designed : a) the idea of a Governing Body in police matters; b) An advisory body in charge of designing and planning police policies; c) Vice ministries specialized in these areas; d) A University also specialized in this matter in which a large investment was made, especially in infrastructure.

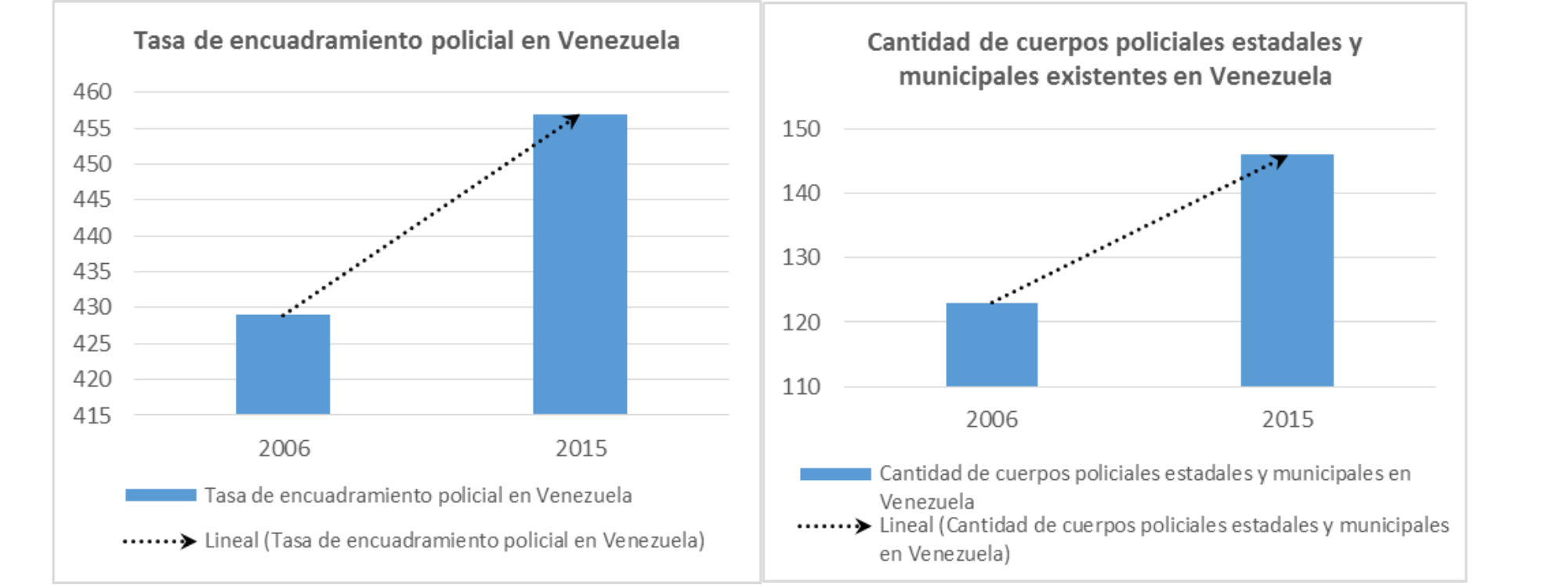

Another result that should be analyzed is police hypertrophyThis is the name given to the accelerated and excessive growth of this institution. Any massification process in the provision of a service must have a rational rhythm, which must be technically and permanently evaluated to ensure quality and prevent the intended remedy from being worse than the disease. Since 2006, based on the process carried out by CONAREPOL, the number of preventive police forces (at the 3 territorial political levels) has increased considerably. International standards for the police involvement rate suggest an average of between 300 and 400 officers per hundred thousand inhabitants. Since 2006, Venezuela was well above this average: 429 police officers per hundred thousand inhabitants (Antillano and Centro for Peace and Human Rights of the UCV, 2007; Antillano, 2014).

Thus, it went from a total of 114,463 police officers in 2006 (Sanjuan, 2012) to more than 140,000 by mid-2015 (Bernal, 2015). This means that the foot of the police force has had an approximate growth of 22.3% in that period, increasing the police cadre rate by 28 more points, to reach 457 police officers per hundred thousand inhabitants, 107 points above the international standard. In 2006 there were 123 state and municipal uniformed police officers, by 2015 that number had risen to 147 (19% increase). The case of the Bolivarian National Police is emblematic, in just six years of creation it reached an approximate number of 14,739 officers. To reach these figures, minimum selection standards are not met, nor training,

This can give indications to make evaluations regarding the efficiency of the police in Venezuela. The current homicide rates and the increasing number of deaths at the hands of the State security forces have been some of the possible consequences of this abrupt increase in the number of police officers in the country.

Finally, there is the entire regulatory block that includes the model, made up of the Organic Law of the Bolivarian National Police Service and Police Corps (LOSPCPNB) (the base law), the Law of the Statute of the Police Function (of the year 2009) , as well as the different norms of a sub-legal nature made up of some 34 resolutions and 25 procedure manuals. However, as has already been said, this does not apply, and actually generates negative concrete results, because what exists de facto is a counter-reformation . It is not a legislative problem, it is a mainly political and institutional problem, and -in a subsidiary way- managerial. The new model embodied in the LOSPCPNB was not implemented, in terms of institutionalization of practices, administration, monitoring, as well as the proper application of protocols and procedures.

This counter-reform, paradoxically, is hidden behind the new model and this regulatory block that is not applied. Both are used to be exhibited in moments of crisis for the police, they make it up, relegitimize it politically, socially and in the media. Its merely declarative use makes routine police practices invisible that end up becoming even more dangerous and harmful. In terms of Merton’s sociology, it could be said that CONAREPOL and the entire police reform process that began in 2006 fulfilled a manifest function of designing a new police model, dignifying the service, making it consistent with the protection of human rights and progressive discourse. Its latent functions are various,military and authoritarian _

In future installments we will answer other questions about the Venezuelan police reform process. If you want to read the full report that serves as the basis for this article, you can find it at this link: https://www.academia.edu/38777597/_Qu%C3%A9_pas%C3%B3_con_la_reforma_policial_en_Venezuela_Preguntas_y_respuestas_b%C3%A1sicas_sobre_el_proceso_en_su_etapa_p%C3%BAber

Publicado originalmente en Provea.