Venezuela’s leader is courting a growing, more socialism-friendly generation in America by co-opting the language of the millennial left.

5 de mayo de 2022

Tony Frangie Mawad

Last summer, a delegation of eight Americans sat down in the grandiose hall of Miraflores Palace in Caracas for a formal meeting with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. The gathering, which was broadcast on Venezuelan state television and shared through the government’s social media networks, was something of a public-relations triumph for Maduro. His presidency is not formally recognized by the United States; the State Department considers it an illegitimate regime, “marked by authoritarianism, intolerance for dissent, and violent and systematic repression of human rights.”

On Venezuelan state television, the American delegation was framed as a bridge-building effort between the two countries. “Venezuela is looking to strengthen ties of brotherhood and solidarity with the American people, with the activists fighting for democracy,” the state TV narrator said.

But the group of Americans sitting across from Maduro weren’t diplomats. The U.S. cut ties with the Maduro government three years ago. Rather, they were representatives of the Democratic Socialists of America — the rising American political organization that includes four House Democrats among its members. The delegates sat deferentially during the appearance and, afterward, expressed admiration for Maduro.

“Who I met is not a dictator,” tweeted Austin González, one of the delegates. “I met a humble man who cares deeply about his people.”

Maduro had invited the DSA delegation for the Bicentennial Congress of the Peoples of the World, a gathering of international groups sympathetic to his regime. While they were there, they toured public-works projects and met with the Venezuelan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They visited the mausoleum for former President Hugo Chávez, the autocratic socialist who Maduro succeeded, and posed with their fists up. They even repeated the regime’s talking points about its historic opponents: Delegate Sean Estelle, for example, referred to former Venezuelan President Carlos Andrés Pérez — a social democrat who had nationalized the oil and iron industries and later became a vocal critic of Chávez — as a “right-winger.”

Hosting the visit was part of a strategy, first undertaken by Chávez and continued by his successor Maduro, to attract American political figures and groups that could support his political interests in the U.S. Now this strategy appears to be targeting young Americans, a demographic with growing political power that’s proven more open to socialism than its older counterparts.

“Americans had really swerved away from leftism after the Cold War,” says Noah Smith, an economist and blogger who has observed the rise of a socialism-friendly generation in the U.S. But thanks in large part to the wave of energy behind Bernie Sanders beginning in 2015, he says, “it’s a cool thing now.”

As Venezuela’s government has spun deeper into autocracy, the nation has become increasingly isolated on the global stage, creating both a humanitarian and reputational crisis for the oil-rich nation. Now, Venezuela’s self-proclaimed radical socialist politics give it a potential alternative point of connection to younger people in the U.S. and elsewhere — one that the Maduro government is clearly trying to leverage.

Today, when the Venezuelan government shares messages on social media and Maduro speaks in public, Venezuelan observers have noted that he increasingly relies on progressive language familiar to young Western leftists. In contrast to older bellicose speeches loaded with macho (and sometimes homophobic) imagery, Maduro is now co-opting the language of “feminism, LGBTI rights, the environment,” says Rafael Uzcátegui, the general coordinator of PROVEA, Venezuela’s most prestigious and oldest human rights organization.

The government is using a “progressive narrative as a possibility for strategic alliances,” though it’s not actually enacting progressive policies to match, says Yendri Velásquez, an LGBTQ activist who works with Amnesty International. Maduro is essentially “wokewashing” — a term usually used to describe corporations advertising the appearance of social consciousness — his government’s image.

Observers and critics in Venezuela also see this as an attempt to reboot the international standing of Chavismo, the political program of Venezuela’s ruling socialists for almost 25 years. Once an ideology that had broader traction in the anti-imperialist global left, Chavismo lost considerable appeal when its namesake Chávez died, and even more as Venezuela spiraled into a democratic and economic crisis.

“The first-world left has always been an important audience for Chavismo because it has certain global, international aspiration,” says Guillermo Tell Aveledo, one of Venezuela’s leading political scientists who specializes in extremist ideologies. Chávez’s government organized festivals that welcomed international parties and activist groups, in the effort to paint his country as a kind of host nation for socialists worldwide. These platforms, like the World Social Forum celebrated in Caracas in 2006, helped Chávez gain allies that would “defend him internationally, amplify his discourse and neutralize international critics,” says Uzcátegui.

Venezuela is one of a long line of far-left authoritarian regimes that have tried to stanch their losses in Washington by appealing to America’s progressive movements. In 1966, for example, Fidel Castro’s Cuba hosted the Tricontinental Conference, where the agenda explicitly stated support for the U.S. civil rights movement, considering it a crucial part of the conference’s supposed anti-imperialist cause. Similarly, Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and Uganda’s Idi Amin Dada attempted to justify their brutality as part of the struggle against European colonialism and apartheid.

Besieged by sanctions and an investigation from the International Criminal Court for alleged human rights violations, Maduro is now experimenting with a new version of this old strategy, building on the growing enthusiasm for leftism among Western youth. The most extreme of this new generation of American leftists have found a home on sites like Twitter and Reddit, where Maduro’s “wokewashing” is designed to earn their retweets and upvotes. Colloquially known as “tankies,” a term originally used disparagingly to denote pro-Soviet British leftists, the members of these online communities of leftists who support foreign authoritarian regimes — many of whom decorate their profiles with a hammer and sickle or emoji flags of countries like Cuba, Venezuela and China — range from the niche to the verified, with hundreds of thousands of followers. Some of their ideas have even spilled to more mainstream personalities like Maduro-defending movie director Boots Riley and Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters.

On TikTok, videos of young American socialists defending Maduro can get tens of thousands of views. For Smith, the politics and economics blogger, “the new tankies have no personal connection with the old tankies” and would more appropriately be called “campists,” a term he uses to denote leftists who support certain countries only for their mere opposition to the U.S. and its allies, while disregarding the actual political situation of these countries.

Members of the DSA delegation did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and the DSA organization did not respond to specific questions for this article.

Members of the DSA delegation said they were visiting Venezuela to “build solidarity” with Maduro’s government, according to their GoFundMe page, despite a series of well-known unsettling facts about the conditions faced by the country’s people. Since Maduro’s rise to power, poverty in Venezuela skyrocketed from 29.4 percent to a staggering 94.5 percent. In 2012, the country’s undernourishment was among the Global South’s lowest; by 2020, Venezuela was the fourth-most-affected country by food insecurity, according to the World Food Programme, behind only Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Afghanistan. From 2010 to 2019, Venezuela dropped by more points on the U.N.’s Human Development Index than any country other than war-torn Syria, Yemen and Libya. From 2016 to 2019, Venezuelan security forces killed 18,000 people, according to Human Rights Watch. The media is censored; there are 240 political prisoners; and democratic institutions have been packed with sympathizers.

While the DSA delegation spent most of its anti-imperialist tourist adventure tweeting about the wonders of Venezuelan socialism, its members stayed in the private five-star luxury hotel Gran Meliá, where one night costs about 100 times the average Venezuelan monthly salary. “View from the dancefloor,” tweeted delegate Jen McKinney with a snapshot, “it’s absolutely beautiful here.”

As Maduro’s PR campaign has seemingly gained a foothold with DSA and other progressive figures and organizations outside Venezuela, the question arises whether he’ll ultimately end up successfully buffing his own international reputation — or simply taking down a number of Western leftists with him.

In Venezuela itself, the DSA trip brought criticism not only from the mainstream opposition to Maduro’s government but also from dissident socialists who see their autocratic president as a blight on the movement. “An organization that denounces racism and police brutality in its country cannot support a government that murders and imprisons Indigenous people for trying to protect their territories from mining depredation,” said Orlando Chirinos, from the Trotskyist Socialism and Liberty Party, who also noted that the DSA delegation stuck to a Maduro-approved itinerary and did not meet with more representative groups.

To Maduro’s critics, there’s a powerful irony in DSA’s praise of the country and its leader: It amounts to a sort of “neocolonialism” in which political activists “from world powers pretend to explain [to Venezuelans or Cubans] their own suffering,” says Keymer Ávila, a researcher from the Central University of Venezuela’s Institute of Criminal Sciences who specializes in police and military brutality.

And DSA isn’t the only left-wing American movement to link arms with Maduro.

In 2015, a year after violently repressing protests against his rule, Maduro was personally honored at the People of African Descent Leadership Summit in New York City, where he received an award for “his labor in favor of the afro-descendants of the United States.” He took a picture with Ayọ Tometi, one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter organization. Three months later, Tometi was in Caracas working as an electoral observer for Venezuela’s parliamentary elections. “Currently in Venezuela,” she tweeted. “Such a relief to be in a place where there is intelligent political discourse.” When the opposition to Maduro won a supermajority, she released a statement: “In a significant blow to the progressive and most impoverished sectors of Venezuela and to global allies … the counter-revolutionaries won control of the National Assembly.” (Tometi did not respond to a request for comment.)

Two years later, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, Venezuela’s Chavismo-supporting Supreme Court, took all power away from the National Assembly, leading to months of protests and riots. Amid this domestic turmoil, Maduro had taken notice of his new U.S. racial justice allies and wanted to keep them on his side. In March 2017, Maduro used the term “white supremacy” — then alien to Venezuelan political discourse — for the first time. During the next five months, the term was used at least six more times in official speeches and communiqués from government officials. In one case, for example, the Maduro government labeled its own attorney general — who had prosecuted the 2014 student protesters — a white supremacist after she joined the opposition against Maduro during a new wave of protests.

Maduro’s “wokewashing” has already paid some dividends. When Juan Guaidó, speaker of the democratic National Assembly, was recognized as president by the U.S. and 60 other countries in 2019, he received the support of most U.S. candidates and members of congress with a few notable exceptions of specific figures associated with the left like Sen. Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.). Jill Stein — the perennial candidate of the U.S. Green Party — played her part too in the Chavismo race strategy, attacking the opposition by tweeting: “Venezuela’s right-wing opposition backed by Trump calls Afro-Venezuelan politicians like Chávez ‘monkeys’ & is known for brutally lynching Black people in the street to ‘send a message.’” Then, she shared a picture comparing the opposition assembly and the Chavista one, purportedly to show a racial divide. Venezuelan critics promptly pointed out both the falsity of her allegations of racist lynchings and that the picture appeared edited to make the opposition appear whiter. Stein did not respond to requests for comment.

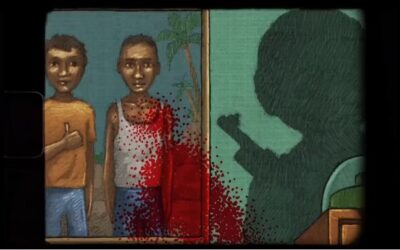

Chavez often framed his anti-imperialist crusade in racial terms, and Maduro has kept that rhetoric alive, in part to cultivate racial-justice supporters in the U.S. However, many observers of Venezuelan politics have noted that Venezuela’s politics are not as easily mappable along racial lines as they are in other countries like the U.S., and research shows that Maduro’s government has engaged in police brutality (with homicides by state security forces three times higher than in the U.S.) that disproportionately targets low-income Black and brown young men.

There are “sectors that condemn police violence in the United States,” says Ávila, “but legitimize and justify the massacre that security forces carry out in Venezuela.”

Maduro’s “wokewashing” isn’t limited to the language of antiracism and decolonization. In recent years, Maduro has also strategically appropriated feminist and pro-LGBTQ rhetoric, too.

Maduro has, for example, used unorthodox expressions of gender-inclusive language when addressing people, and his party has created offices for “sex diversity” and a parliamentary subcommittee for LGBTQ issues. His Assembly has publicly met with pro-abortion groups, and political ads from the ruling party now mention things like “reproductive rights.” Chávez and Maduro are repeatedly described in government broadcasts and texts as “feminist presidents.”

As with his racial politics, Maduro’s progressive gender displays are seen by domestic critics as purely “propaganda strategies,” says Yendri Velásquez, the LGBTQ activist. While many Latin American countries legalized same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples, in Venezuela both remain illegal. LGBTQ people still cannot openly serve in the military. And while Venezuela was the first Latin American country to recognize transgender identities in 1977, since 1998 — the year Chávez first won the presidency — not one trans citizen has been allowed to legally change their gender identity, though transgender people were given the ability in 2016 to use pictures after their transitions in official documents and IDs. Meanwhile, the government has deepened its ties with evangelical churches, which increasingly represent a strong electoral force, and Venezuela’s abortion ban remains among South America’s most restrictive, while the country has one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates in Latin America.

“Chavismo has become an embarrassment” for the international left, says Uzcátegui, the human rights official. Even Bernie Sanders, for example, denounced Maduro as a “tyrant” in 2019 after being pressed and criticized for previously stopping short of calling him a “dictator.”

Yet while some, like Sanders, among the growing U.S. left are beginning to see through Maduro’s messaging of socialist solidarity, other more stalwart Chavismo sympathizers and apologists have recently achieved important positions in American politics: After the U.S. government recognized Guaidó as president of Venezuela in 2019, Rep. Ilhan Omar falsely denounced the National Assembly’s struggle against Maduro as “a U.S.-backed coup,” while also falsely describing the opposition as “far right.” She has since repeatedly blamed American sanctions for “devastation” in Venezuela without mentioning Chávez and Maduro’s widespread corruption and mismanagement. Spokespeople for Sanders and Omar declined to comment.

Although their congressional contingent is currently small, as millennial socialists and groups like DSA make further inroads into American politics, the chances of more Chavismo-friendly politicians taking office across the country — and perhaps getting a chance to nudge U.S. foreign affairs — increase, highlighting a possibly troubling future for Venezuela’s democratic struggle.

“To some extent, there is a romanticization of Maduro” among some in the U.S. left, says Gabriel Hetland, a professor of Latin American studies at the University of Albany who has studied Venezuela since 2007. “There’s good motives: a critique of U.S. imperialism,” says Hetland, who identifies as a leftist and says he remains sympathetic to earlier forms of Chavismo and opposes sanctions. But “any serious leftist should not be supporting this government at all,” he says, pointing to Maduro’s “ecological” destruction, widespread repression and “pro-market” shifts in recent years.

“Institutional violence and human rights violations must always be condemned energetically,” says Ávila. “There aren’t good human rights violators, and their behavior cannot be justified in any way. That double standard to condemn some and justify the same excesses in others makes an enormous damage to societies, states and politics itself.”

Publicado originalmente en: Politico